Zi Mu Zhang

Before colonialism, Ecuador was part of the vast Inca Empire, which ruled much of northern South America. The Inca built an impressive road network and developed infrastructure like the famous ceremonial site of Machu Picchu. Ecuador’s indigenous people were skilled architects and engineers, constructing buildings that have withstood centuries of natural disasters. However, the arrival of Spanish colonizers in the 16th century marked the beginning of profound changes for Ecuador’s land and its people.

Ecuador’s once-thriving ecosystems have become degraded landscapes, scarred by deforestation, polluted waterways, and eroding land. The roots of these problems can be traced back to Spanish colonization, when European powers introduced large-scale mining operations and resource extraction practices that laid the groundwork for the country’s future industries. Today, mining, petroleum extraction, and hydropower projects continue to exploit Ecuador’s natural resources, often at the expense of its most vulnerable populations: indigenous communities.

Just as Spanish colonizers once extracted Ecuador’s gold and silver, modern industries strip the country of its remaining natural wealth, leaving behind devastated environments and displaced communities. Indigenous groups, in particular, who have lived sustainably off the land for centuries, are now facing the brunt of this environmental destruction. They are often forced to contend with contaminated rivers, eroding landscapes, and poor air quality while receiving little benefit from the profits reaped by these industries.

This paper will explore how modern industries—namely mining, petroleum extraction, and hydropower—are contributing to Ecuador’s environmental degradation, with a focus on how these practices disproportionately impact indigenous communities. Through case studies of regions like Al Pasa and El Coca, we will examine the long-term effects of these industries and the urgent need for a more sustainable approach to development in Ecuador.

Mining

Mining in Ecuador, a practice initiated by Spanish colonizers over 500 years ago, continues to cause severe environmental degradation today. Spanish colonizers introduced large-scale mining to exploit valuable natural resources such as gold and silver, which set the foundation for the ongoing resource extraction that continues in modern times. The legacy of these practices has left a profound environmental and social impact on the country, particularly in indigenous areas.

In this section, the Al Pasa site serves as a case study to explore the environmental and social effects of mining in Ecuador.

Erosion and Air Pollution from Mining

The Al Pasa site, located in the Andes Mountains, has been exploited for stone mining since the colonial era. The stones extracted from this region were used to build cities like Quito, leaving the hills surrounding Al Pasa stripped bare. The removal of vegetation has destabilized the land, making the region particularly vulnerable to erosion. According to field data collected from local residents, the loss of vegetation has significantly contributed to the worsening environmental conditions.

One of the most critical environmental issues in Al Pasa is the exposure of unstable volcanic ash layers, which, when disturbed by mining activities, release harmful PM10 particles into the air. These fine particles pose severe health risks to the local population, including respiratory illnesses and skin conditions. Residents interviewed during the field research reported frequent occurrences of coughing, breathing difficulties, and skin rashes, which they attributed to the dust generated by mining operations. The air pollution also affects neighboring towns and even reaches Quito, contributing to declining air quality in the region.

Field observations revealed that illegal mining activities have further exacerbated the environmental damage. Local community members reported that illegal miners operate with impunity, leading to deforestation and unchecked land degradation. The Kichwa people in the area expressed frustration during interviews, stating that despite numerous complaints, government intervention has been minimal, leaving them to deal with the environmental crisis alone.

Water Contamination from Mining Activities

Water pollution is another critical issue in Al Pasa, where the extraction of copper and other metals has led to significant contamination of nearby rivers. Field research revealed that the water in the area contains high levels of heavy metals, which pose a serious threat to both human health and agriculture. Many residents have turned to well water for drinking and household purposes, but even these water sources are at risk, as pollutants continue to seep into underground water layers.

Interviews with farmers in Al Pasa revealed that crop yields have decreased dramatically due to contaminated water used for irrigation. Local livestock have also suffered from the polluted water, with many animals developing skin lesions and other health problems. These issues have had a devastating impact on the local economy, as agriculture and livestock farming are primary sources of income for the community. During the field research, one local farmer remarked, “We can no longer trust the water. It has poisoned our crops and our animals, and we fear it is poisoning us too.”

Impact on Local Communities and Economic Disparities

The Kichwa community in Al Pasa has been disproportionately affected by the environmental degradation caused by mining. Field research found that 70% of the population in the area is employed in the mining industry, yet the economic benefits have been minimal. Local residents expressed their concerns in interviews, noting that while they rely on mining for employment, the health risks and environmental destruction outweigh the financial gains. One community leader shared, “We work the land, but the land is killing us slowly.”

In response to these challenges, the community has turned to alternative solutions, such as promoting tourism based on the region’s rich Inca archaeological heritage. However, transitioning away from mining has proven difficult due to the community’s deep reliance on mining for income. Field research revealed that tourism efforts are still in their early stages, and the community lacks the necessary infrastructure to make a significant economic shift. Nevertheless, the Kichwa people remain hopeful that they can create a more sustainable future for their children.

The loss of vegetation and continued deforestation has worsened the erosion problem in the region. Without plant roots to stabilize the soil, erosion continues to worsen, threatening both the stability of the land and the livelihoods of those who depend on it. Residents also noted that volcanic ash carried by the wind has reached Quito, affecting air quality in the city and contributing to broader environmental concerns across Ecuador.

Long-Term Environmental and Social Costs of Mining

The environmental consequences of mining in Al Pasa are not limited to physical degradation; the social costs are also significant. The Kichwa community has borne the brunt of the environmental damage, facing both health problems and the destruction of their ancestral lands. Field research revealed that many Kichwa residents feel abandoned by the government, with one local elder stating, “We’ve been forgotten. They only come when they want something from us, but they leave us with nothing but dust and sickness.”

While mining has historically been a major driver of Ecuador’s economy, the economic benefits have largely bypassed indigenous communities, who suffer the consequences of poor health, polluted water, and degraded land. The environmental and social challenges posed by mining have laid the groundwork for even greater problems with the rise of petroleum extraction in the 20th century, as Ecuador became increasingly reliant on oil to fuel its economy.

Petroleum

Petroleum extraction is one of the most critical environmental issues facing Ecuador, particularly in regions like El Coca and surrounding towns near the Amazon Basin, where oil extraction activities are most concentrated. While oil is a vital contributor to Ecuador’s economy, the environmental and social costs are devastating, especially for local indigenous communities who bear the brunt of pollution and environmental degradation.

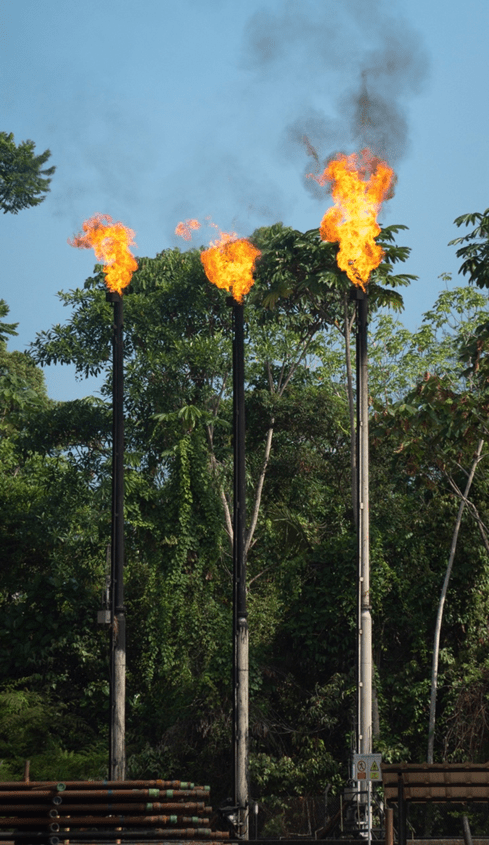

In this section, El Coca and its surrounding areas serve as a case study to explore the broader environmental impacts of petroleum extraction in Ecuador. The harmful practices associated with this industry, such as gas flaring, oil spills, and improper waste disposal, have left a lasting impact on the environment and the lives of local people.

Air and Water Pollution from Petroleum Extraction

One of the most damaging practices in El Coca is the burning of natural gas at petroleum sites. Known locally as “the lighters of death,” these gas flares are used to burn off excess natural gas, which is considered too expensive to transport. This practice releases large quantities of greenhouse gases and toxic chemicals, including sulfur dioxide, into the atmosphere. According to interviews with local residents conducted during the field research, many communities suffer from respiratory illnesses and skin conditions linked to long-term exposure to these pollutants.

Residents in El Coca report that air pollution is only part of the problem. The improper disposal of crude oil poses a significant environmental threat, as companies often dump excess crude oil into pits, which are then covered with soil. Over time, this crude oil seeps into the surrounding soil and water, contaminating local water supplies. Farmers in El Coca have witnessed decreased crop yields and reported health problems among their livestock, which have been linked to the consumption of contaminated water and plants.

Field research conducted in El Coca also revealed that many communities have been forced to switch to well water for drinking and household use, as rivers and streams have become too polluted. However, even these water sources are at risk, as pollutants from petroleum extraction seep into underground aquifers over time, threatening the long-term sustainability of these water reserves.

Oil Leaks, Spills, and Infrastructure Failures

Frequent oil leaks and spills further compound the environmental damage caused by petroleum extraction. Due to seismic activity, poor maintenance, and aging infrastructure, pipelines running through the Amazon are prone to ruptures. Local residents reported multiple instances of oil spills that went unnoticed for days, allowing thousands of gallons of crude oil to contaminate nearby rivers, wetlands, and agricultural land.

Our field research documented one such spill in San Carlos, a town near El Coca, where local fishermen described how the Napo River had become heavily polluted with oil. Residents stated that they had stopped fishing due to contamination, and many expressed concerns about their health after consuming fish from these waters. Additionally, some residents noted a strong odor coming from the river, making the water unusable for daily activities such as cooking, washing, or farming.

One of the most notable incidents occurred when an oil spill from the OCP pipeline went undetected for several days, contaminating large portions of the Coca River. Field data showed that this spill had devastating effects on the local ecosystem, wiping out several species of fish and aquatic plants, and leaving local communities without access to clean water for weeks. This has further strained indigenous populations who depend on the river for their livelihoods.

Health Impacts on Indigenous Communities

The health impacts of oil extraction are particularly severe for indigenous populations living near petroleum sites. Field data from El Coca and surrounding towns revealed abnormally high rates of cancer, particularly among children and the elderly, who are most vulnerable to the toxins released during oil extraction. According to local health officials, cancer rates in some communities are five times higher than the national average.

Interviews conducted during the field research revealed that local residents attribute the high cancer rates to long-term exposure to oil spills, contaminated water, and toxic chemicals used in petroleum extraction. Many residents reported skin rashes, respiratory illnesses, and digestive problems that they believe are linked to the pollutants from oil extraction sites. Children are especially vulnerable, with many families reporting high incidences of asthma and other lung-related diseases.

In addition to these direct health impacts, petroleum extraction has disrupted the traditional ways of life for many indigenous groups. Fishing, hunting, and agriculture—the primary means of sustenance for these communities—have become increasingly difficult due to the contamination of rivers, forests, and agricultural land. Field observations show that some families have been forced to leave their ancestral lands in search of safer, cleaner environments, further eroding their cultural identity and connection to the land.

Uneven Distribution of Petroleum Profits

Despite the economic importance of oil to Ecuador, the benefits of oil extraction are unevenly distributed. While oil revenues contribute to national infrastructure projects, local communities near extraction sites see little economic benefit. During interviews, residents of El Coca described feeling abandoned by both the government and oil companies. Many locals noted that despite living in one of the most resource-rich areas of Ecuador, they lacked basic infrastructure, such as clean water and electricity.

Field research revealed that oil extraction has exacerbated economic inequalities in the region. Many local families struggle to make ends meet, as the environmental degradation caused by oil spills has reduced their ability to farm, fish, or rely on other natural resources for income. The government’s failure to properly regulate oil companies or hold them accountable for environmental damage has only deepened the sense of injustice among local residents.

Efforts to hold oil companies accountable have largely been unsuccessful. Although there have been some legal victories in the past, such as the landmark case of Texaco/Chevron, in which some communities received compensation for environmental damage, most legal efforts are delayed or dismissed. Interviews with local legal advocates revealed that many cases are stalled in court, leaving indigenous communities to fend for themselves against powerful oil companies.

The environmental degradation caused by petroleum extraction in regions like El Coca has had profound consequences for local communities. The health problems, polluted water sources, and economic disparities in the region highlight the long-term costs of oil extraction, which disproportionately affect Ecuador’s indigenous populations. While petroleum remains a central component of Ecuador’s economy, the industry’s failure to address these environmental and social impacts continues to exacerbate the inequalities that began during the colonial era.

As Ecuador grapples with the destructive effects of oil extraction, the country has also turned to hydropower as a potential solution to its energy needs. However, as with petroleum, hydropower projects come with significant environmental consequences, which will be explored in the next section.

Hyropower

Hydropower is often viewed as a cleaner alternative to fossil fuels, but large-scale projects can cause significant environmental and social consequences. One such project is the Coca Codo Sinclair Hydropower Station, Ecuador’s largest hydroelectric facility, located near El Chaco in the Napo Province. Completed in 2016, this project was designed to supply around 30-40% of Ecuador’s electricity needs, reducing the country’s dependence on imported energy. However, the project has also led to severe environmental degradation, particularly in the form of erosion and habitat disruption, and has caused significant harm to nearby communities.

Erosion and Sediment Buildup

One of the most significant environmental impacts of the Coca Codo Sinclair project is erosion. Field research conducted in St. Louis, a small town located just 20 meters from the rapidly eroding riverbanks of the Coca River, revealed that local residents live in constant fear of losing their homes and land. As the dam traps sediment that would naturally flow downstream, the river’s natural processes are disrupted, leading to accelerated erosion. Over time, riverbanks become unstable, and the land loses its ability to resist erosion.

Residents in St. Louis reported that the speed at which the land is disappearing has become alarming, with the riverbank shrinking by nearly 40 meters in the past decade. The erosion has already claimed several homes and farmlands, forcing families to relocate to higher ground. The community expressed frustration during interviews, noting that government assistance has been minimal, with relocation efforts only available to the poorest families, leaving many to fend for themselves as their lands continue to erode.

In addition to erosion, the sediment buildup behind the dam is causing further problems. As sediment accumulates, it reduces the dam’s storage capacity and affects the efficiency of the turbines that generate electricity. Interviews with engineers working on the project revealed that the turbines often experience strain during the dry season when water flow is insufficient, making it difficult to maintain consistent electricity generation. Despite its intended benefits, Ecuador continues to import energy from neighboring countries to meet its electricity needs, highlighting the limitations of the project.

Loss of Biodiversity and Habitat Fragmentation

The Coca Codo Sinclair project has also resulted in the fragmentation of habitats and a reduction in biodiversity. According to interviews with local environmental experts, the dam has severely disrupted the migratory patterns of fish and other aquatic species that depend on free-flowing rivers. Several species of fish native to the Coca River have seen sharp declines in their populations, as they can no longer migrate upstream to spawn.

Field observations confirmed that local wildlife has been affected by changes in water flow and quality. Indigenous communities that rely on the river for fishing have reported that many fish species, once abundant, are now disappearing. As a result, the communities that depend on these species for their livelihoods have suffered economic losses. Additionally, the loss of biodiversity extends beyond aquatic species. Vegetation and animal life near the river have been impacted by the changes in water flow, leading to further ecosystem disruption.

Interviews with conservationists in El Chaco highlighted concerns that the hydropower project has not taken into account the long-term ecological damage it is causing. The area, once rich in biodiversity, has become a fragmented landscape where ecosystems are struggling to adapt to the new conditions imposed by the dam. The Coca Codo Sinclair project serves as a stark reminder that even renewable energy projects can have devastating consequences for local ecosystems.

Impact on Local Communities and Indigenous Displacement

The environmental degradation caused by the Coca Codo Sinclair hydropower station has had profound consequences for nearby communities, particularly inSt. Louis, where the erosion is most severe. Residents described the psychological toll of watching their land slowly disappear. One resident, during an interview, remarked, “We used to live by the river, but now the river is coming to take our homes away.” Many families are worried about the future, unsure of when they will be forced to leave.

The government’s relocation efforts have been insufficient, with only a small number of families receiving assistance to move to safer areas near El Chaco. Indigenous communities, who hold their ancestral lands in deep spiritual and cultural regard, are particularly reluctant to leave despite the risks. For many indigenous families, their connection to the land is tied to their cultural identity, making relocation an emotionally and culturally painful process.

Field research documented that the erosion also threatens Ecuador’s vital infrastructure. Oil pipelines that run alongside roads near the river have been disrupted by landslides and erosion, causing frequent shutdowns in oil transmission. These disruptions have economic consequences, as oil production is a major contributor to the national economy. The instability of the land near the hydropower station highlights the broader risks posed by large-scale infrastructure projects that fail to account for long-term environmental impacts.

Social and Economic Inequities

While hydropower plays an important role in Ecuador’s energy strategy, the social and economic costs of large-scale projects like Coca Codo Sinclair are significant. Many of the families living near the dam have experienced economic hardship due to the environmental damage caused by the project. Indigenous communities, in particular, have been disproportionately affected, as they are often left with little recourse after their lands are taken or destroyed.

Interviews with local leaders revealed deep resentment toward both the government and the companies involved in the project. One community leader from St. Louis commented, “We were promised that this project would bring prosperity to our people, but all it has brought is destruction.” While the economic benefits of hydropower are felt at the national level, with revenues used for infrastructure and development projects, local communities receive little in return, often left to deal with the environmental degradation on their own.

As with other extractive industries, the hydropower project has exacerbated existing economic inequalities. The benefits of the Coca Codo Sinclair project have primarily gone to foreign investors and the national government, while local communities are left to bear the environmental and social costs. Field interviews revealed that many residents feel abandoned by their own government, with little hope for compensation or improvement in their living conditions.

Environmental and Social Trade-offs

Although hydropoweris seen as a cleaner alternative to fossil fuels, the environmental damage and displacement caused by projects like Coca Codo Sinclair show that even renewable energy sources can replicate the exploitative practices of colonial-era resource extraction. Local communities are forced to endure displacement, loss of livelihoods, and environmental degradation while seeing little of the economic benefits. The project highlights the urgent need for more sustainable energy development that prioritizes the well-being of local communities and the preservation of Ecuador’s ecosystems.

Conclusion

Ecuador’s environmental challenges today are deeply rooted in centuries of resource extraction, beginning with Spanish colonization and continuing with modern industries like mining, petroleum extraction, and hydropower. Indigenous communities, who have lived sustainably on this land for generations, now face the devastating consequences of deforestation, water contamination, and habitat destruction. Over time, Ecuador’s natural resources have been continuously extracted—first by the Europeans, then by Americans through mining, and now by Chinese companies through oil extraction.

What would happen if these resources were exhausted? What would happen if environmental degradation became so severe that indigenous people could no longer live in their ancestral lands? While foreign powers might move on to exploit resources elsewhere, the indigenous communities would be left with nowhere to go, as they are intricately tied to the land that has sustained them for generations.

As the name of a local community elementary school suggests, Ecuador should be a place that is “SUMAK ALLPA” in Kichwa, meaning “beautiful earth.” The beautiful rainforest, which has been a target for external exploitation, should not serve only the interests of foreign powers or national elites. Instead, it must be protected and sustained for the benefit of its local people. If Ecuador continues to prioritize maximum profit and efficiency without regard for long-term sustainability, it will lose the very resources and natural beauty that define the country.

The Kichwa concept of “SUMAK ALLPA” reflects a vision of balance and respect for nature—an approach that could guide Ecuador toward a future that embraces both environmental protection and economic growth, ensuring a more equitable and sustainable path for all.