Author: Jin YAN

Abstract

Glacier retreat is among the most visible indicators of contemporary climate change, reshaping high-mountain hydrology, ecosystems, and hazard regimes. This comparative paper examines the Tasman Glacier (Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park, New Zealand) and the Weigledangxiong Glacier (A’nyêmaqên/Anyemaqen Mountains, Qinghai, China). Integrating peer-reviewed remote sensing studies and field interviews with local stakeholders, we analyze retreat trends, climate drivers, and environmental and social impacts, and discuss adaptation pathways. Results show rapid and ongoing ice loss at both sites, primarily driven by atmospheric warming; proglacial lake expansion and debris–ice–water interactions further accelerate retreat at Tasman, while rising temperatures, changing precipitation phase, and surface darkening intensify ablation at Weigledangxiong. Consequences include altered runoff seasonality, grassland stress, and elevated geo-hazard risks. We argue for multi-level responses—scientific monitoring, risk governance, community engagement, and emissions mitigation—tailored to local socio-ecological contexts.

I. Introduction

Global and Regional Context

The 2015 Paris Agreement (signed on 22 April 2016) set the goal of holding the increase in global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit warming to 1.5 °C, a threshold beyond which climate impacts are expected to intensify markedly. If present emission trajectories persist, end-of-century warming could reach ~2.7 °C. The Tibetan Plateau—often described as a driver and amplifier of climate change—has experienced decadal warming roughly twice the global average, rendering its cryosphere and ecosystems particularly sensitive (Qin et al., 2018).

Study Areas

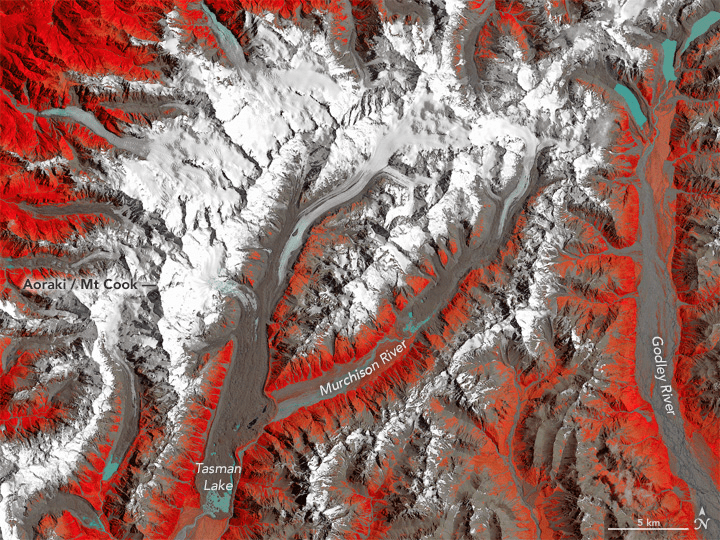

In New Zealand’s Southern Alps, the Tasman Glacier is the country’s largest (~23.5 km long with an area >100 km²) and has been intensively studied since the 1970s for its rapid retreat and proglacial lake expansion (Dykes et al., 2011). In China, our focus is the A’nyêmaqên (Anyemaqen) Range, a major glaciated massif in the headwaters of the Yellow River. The range, rather than a single mountain, forms an eastern spur of the Kunlun. It hosts 18 peaks above 5,000 m, with the main summit Ma Qing Gangri at 6,282 m; the total glacierized area is on the order of ~125 km², and the massif is encircled on three sides by the Yellow River, acting as a crucial ecological and hydrological barrier for the basin. Meteorological observations at summit stations indicate exceptionally high precipitation (≈1,200–1,300 mm yr⁻¹) in the Yellow River source region. Within this system, the Weigledangxiong Glacier—located on the northeastern flank of the range—is the longest valley glacier in the Yellow River basin (length ~10 km; area ~12 km²). For local Tibetan pastoralists, Anyemaqen (the range) is the sacred mountain; Weigledangxiong is one representative glacier within this sacred landscape.

By comparing Tasman and Weigledangxiong, we examine retreat trends, climate drivers, environmental impacts, and social significance. We triangulate academic literature with field interviews to reveal both the physical processes and human dimensions of glacier change.

II. Glacier Retreat Trends

Tasman Glacier

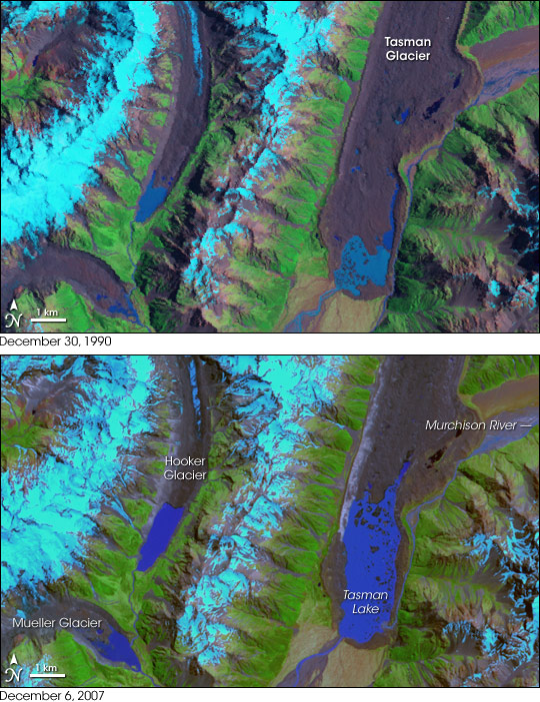

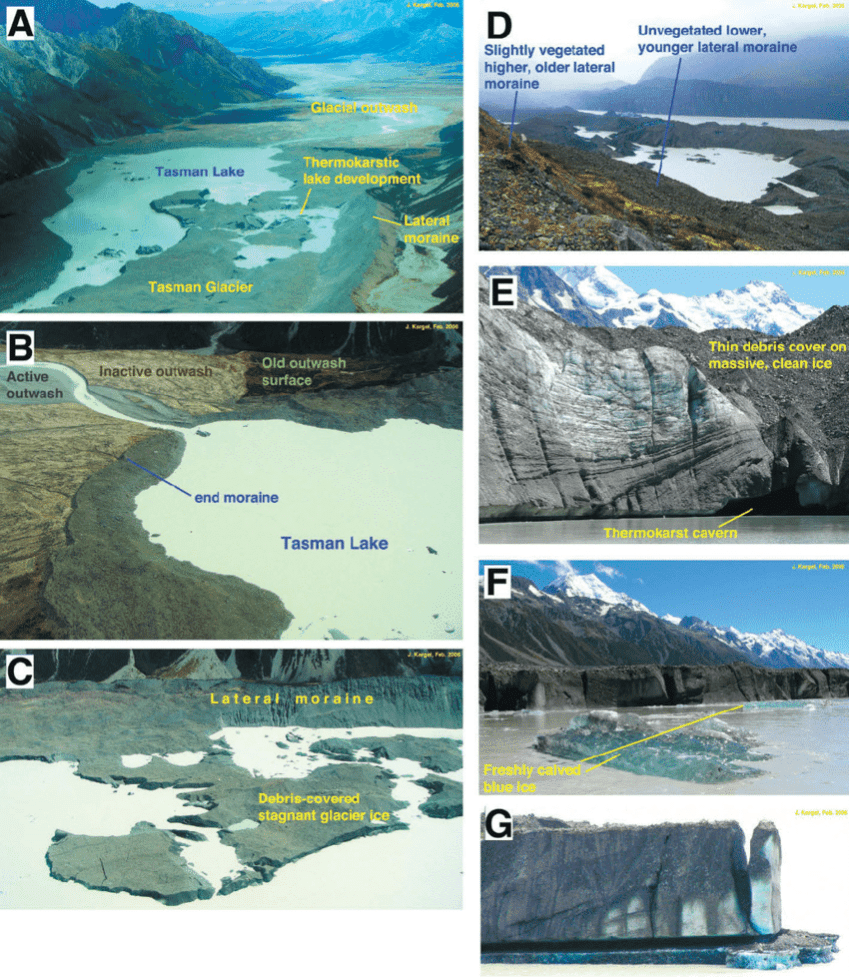

In recent decades, the Tasman Glacier has retreated at remarkable rates. Remote-sensing analyses show that since the 1990s, its terminus retreat has locally reached ~180 m yr⁻¹. Between 2000 and 2008 alone, the glacier retreated by ~3.7 km, while a small pond at the terminus expanded into Tasman Lake extending ~7 km by 2008 (Dykes et al., 2011). Since the Little Ice Age, the glacier has lost on the order of ~4.5 km³ of ice (Carrivick et al., 2020).

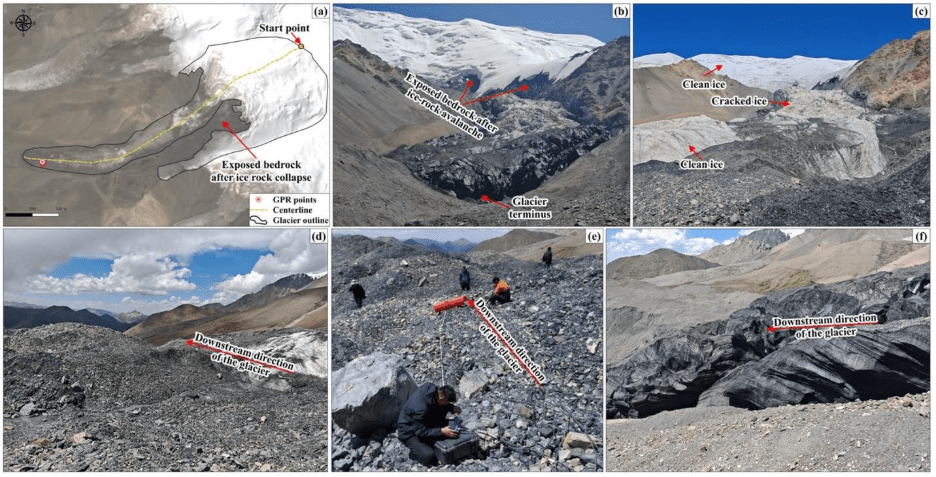

Weigledangxiong Glacier

Across the A’nyêmaqên region, glacier area decreased by ~29.4 km² (1985–2017), with an average annual mass balance of −0.71 m w.e. yr⁻¹ (Li et al., 2022). From 2002 to 2023, mean glacier surface elevation fell by ~7.88 m, with stronger declines on southern aspects (Li et al., 2024). Field interviews corroborate these observations. A pastoralist (Guoqing) recalled: “In two decades, when the glacier is gone, the Yellow River may run completely dry.” This local testimony aligns with satellite-based monitoring, reinforcing a convergent line of evidence for retreat.

III. Climate Drivers

Temperature Rise

Global warming is the primary driver of glacier retreat at both sites. In the A’nyêmaqên region, average annual temperatures from 2005 to 2022 were ~−4.0 °C, increasing at ~0.3 °C per decade (Qin et al., 2018). Warmer summers lengthen the ablation season and reduce snowfall frequency, accelerating mass loss. In New Zealand, while short-lived advances have occurred during episodic regional cooling (Mackintosh et al., 2017), long-term warming dominates mass balance trajectories. At Tasman, the development of a deep proglacial lake amplifies thermal undercutting and calving, accelerating retreat (Dykes et al., 2011).

Precipitation and Surface Processes

Precipitation changes operate differently at the two sites. In Qinghai, declining snowfall fractions and more frequent summer rainfall reduce net accumulation on glaciers; in addition, dust deposition and associated surface darkening lower albedo and enhance energy absorption, reinforcing ablation (Zhang et al., 2021). Despite a recent increasing trend in precipitation across the Anyemaqen region (2014–2020 mean precipitation +23 mm; concurrent mean air temperature increase ~1.6 °C), glaciers remain in net retreat—indicating that enhanced accumulation cannot offset warming-driven ablation; melt exceeds mass gain. [Added per teacher guidance; see Wang et al., 2015] In the Southern Alps, precipitation variability influences interannual mass balance, but at Tasman, the combined effects of warming and lake–ice dynamics outweigh direct precipitation impacts (Dykes et al., 2011).

IV. Water-Resources Impacts

Glacial meltwater is a key component of freshwater supply in both regions. In the Yellow River headwaters, meltwater contributes ~15–25% of dry-season runoff (Yao et al., 2012). Ongoing retreat at Weigledangxiong threatens this stability. As Guoqing warned: “In two decades, when the glacier is gone, the Yellow River may run completely dry.” Beyond short-term “pulse” supply during intensified melt, glaciers perform a regulatory function akin to natural reservoirs—releasing water in summer and sustaining baseflow in winter. Thus, long-term glacier loss compromises not just quantity but seasonal buffering capacity, heightening downstream drought risk in the Sanjiangyuan region.

In New Zealand, Tasman Lake’s expansion has altered downstream hydrology and sediment transport (Carrivick et al., 2020). While meltwater still feeds rivers, diminishing ice reserves suggest declining reliability of runoff over the coming decades.

V. Grassland and Ecosystem Impacts

In the A’nyêmaqên region, reduced summer meltwater constrains alpine-meadow and wetland hydrology, stressing grasslands. Continuous heat can wither newly sprouted grasses, while intense rainfall spikes surface runoff and erosion. A pastoralist (Pu Wangjie) noted: “If it doesn’t rain or snow, the whole grassland fails; it’s getting hotter, and the glacier shrinks each year.” These dynamics elevate grazing pressure and degrade rangeland function. In New Zealand, Tasman’s expanding proglacial lake creates novel aquatic habitats but also reshapes near-lake ecotones and destabilizes shorelines, affecting biodiversity and tourism.

VI. Natural-Hazard Risks

Retreating glaciers elevate geo-hazard risks. In Qinghai, more frequent landslides and floods are linked to melt-weakened slopes and extreme precipitation. A resident (Liu Nan) recalled a major landslide that destroyed roads near A’nyêmaqên, while Pu Wangjie noted that floods repeatedly wash out access routes. Notably, the Xiaomagou glacier sector of Anyemaqen experienced four large-scale collapse events—in February 2004, October 2007, October 2016, and July 2019—illustrating chain-type hazard processes under sustained warming (Wang, Zhang, & Wang, 2022). At Tasman, rapid calving into a deep lake can generate large waves (“iceberg tsunamis”) and trigger bank failures, posing risks to visitors and infrastructure (Dykes et al., 2011).

VII. Response and Intervention Measures

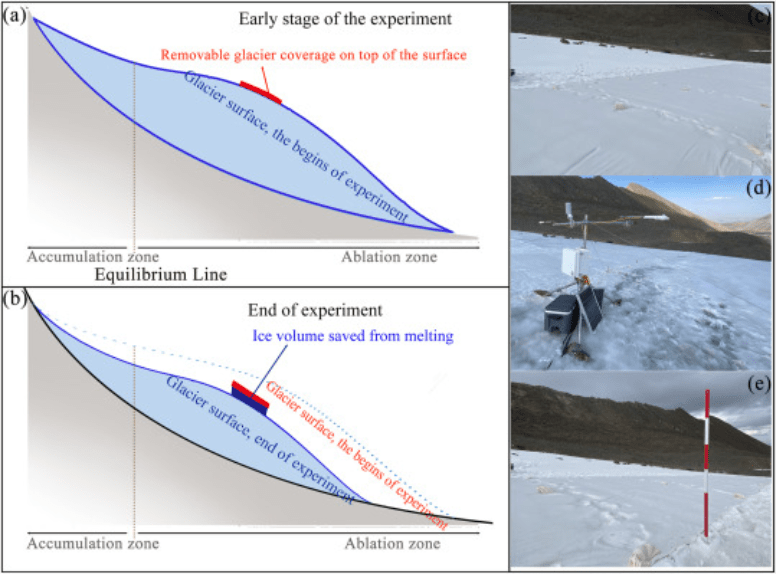

Adaptation pathways differ by context. In A’nyêmaqên, experimental interventions include artificial snowmaking and seasonal coverage of ice surfaces with reflective geotextiles to enhance albedo and reduce melt (Li et al., 2024). Environmental governance blends policy and culture: forest rangers organize waste management and rangeland protection; monasteries disseminate conservation ethics through chants and songs; and NGOs support community-based actions. In New Zealand, responses emphasize monitoring and risk governance—satellite and UAV remote sensing, lake-level observation, hazard mapping for potential glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), and visitor safety management (Garcia, 2022).

VIII. Conclusion

The Tasman and Weigledangxiong glaciers illustrate the profound and heterogeneous impacts of climate change on high-mountain cryospheres. Despite differing geographies and cultures, both glaciers are shrinking rapidly under atmospheric warming. Yet consequences manifest locally: in Qinghai, glacier retreat intersects with pastoral livelihoods, the sacred-mountain significance of Anyemaqen, and the water security and seasonal regulation of the Yellow River[6]; in New Zealand, it reshapes alpine landscapes, reorganizes hydrology, and generates tourism-related hazards. Framed against the Paris Agreement’s 1.5–2 °C thresholds, these findings underscore the urgency of transnational emissions mitigation and multi-level adaptation—scientific monitoring, risk governance, and culturally grounded community engagement—to safeguard ecosystems, water resources, and human well-being.

References (APA 7th)

1.Carrivick, J. L., Davies, B. J., James, W. H. M., Quincey, D. J., Glasser, N. F., Lorrey, A. M., … & Chinn, T. J. (2020). Ice thickness and volume changes across the Southern Alps, New Zealand. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 16352. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73134-6

2.Chinn, T., Salinger, J., Fitzharris, B., & Willsman, A. (2014). Glacier retreat in New Zealand’s Southern Alps. Global and Planetary Change, 121, 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2014.06.008

3.Dykes, R. C., Brook, M. S., & Winkler, S. (2011). Twenty-First Century Calving Retreat of Tasman Glacier, Southern Alps, New Zealand. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 43(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1657/1938-4246-43.1.1

4.Garcia, R. (2022). Mapping the retreat of the debris-covered Tasman Glacier terminus using remote sensing (Master’s thesis). University of Arizona Repository. https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/665584

5.Greenpeace East Asia. (2019). Melting earth: Climate change and glacier retreat on the Tibetan Plateau. Greenpeace. https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-eastasia-stateless/2019/11/1c73bd5d-1c73bd5d-melting-earth.pdf

6.Li, Z., Zhang, G., Zhang, M., Wang, W., & Zhou, H. (2022). Reconstructed annual glacier surface mass balance in the Anyemaqen Mountains, Yellow River source, based on snow line altitude. Remote Sensing, 14(8), 1826. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14081826

7.Li, Z., Zhang, G., Wang, W., & Zhou, H. (2024). Changes in glacier area and surface elevation in the Anyemaqen Mountains from 2002 to 2023. Remote Sensing, 16(13), 2446. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs16132446

8.Mackintosh, A. N., Anderson, B., Lorrey, A. M., Renwick, J., Frei, P., Dean, S. M., … & Buckley, K. M. (2017). Regional cooling caused recent New Zealand glacier advances in a period of global warming. Nature Communications, 8, 14202. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14202

9.NASA Earth Observatory. (2017). Retreat of the Tasman Glacier, New Zealand [Satellite images]. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/90087/retreat-of-the-tasman-glacier

10.Qin, D., et al. (2018). Report on climate and environmental change in Western China: 2018. Beijing: Science Press.

11.Robertson, C., Benn, D. I., Brook, M. S., & Carrivick, J. L. (2012). Proglacial lake development and associated hazards in Aoraki/Mt Cook National Park, New Zealand. Geomorphology, 139–140, 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.10.020

12.Yao, T., Thompson, L. G., Yang, W., Yu, W., Gao, Y., Guo, X., Yang, X., Duan, K., Zhao, H., Xu, B., Pu, J., Lu, A., Xiang, Y., Kattel, D. B., & Joswiak, D. (2012). Different glacier statuses with atmospheric circulations in Tibetan Plateau and surroundings. Nature Climate Change, 2(9), 663–667. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1580

13.Zhang, G., Li, Z., Wang, W., Zhou, H., & Li, J. (2021). Glacier changes in the source region of the Yellow River, Tibetan Plateau, during 1970–2015. Journal of Glaciology, 67(263), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2021.49

14.Wang, K., Yang, T., He, Y., et al. (2015). Relationship between glacier change and climate change in the Anyemaqen Mountains over the recent 30 years. Research of Soil and Water Conservation, 22(3), 300–303, 308.

15.Wang, Z., Zhang, T., & Wang, W. (2022). Multi-episode glacier-collapse chain disasters in the Anyemaqen Mountains: A review and outlook. Journal of Beijing Normal University (Natural Science), 58(6), 950–962.