Author: JinYan, Yingrong Feng, Zhenfan Yang ,YuanJiang, Xiwen Bai (No Particular Order)

The Sanjiangyuan Region, also known as the “Source of Three Rivers,” is located on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and serves as one of China’s most critical ecological security barriers. Its vast high-altitude grasslands, fragile alpine ecosystems, and unique cultural landscapes make it a vital carbon sink in the fight against global warming. However, this ecological role is increasingly challenged by human activities such as waste disposal, tourism, livestock management, and religious practices. While these activities contribute to economic growth and support local livelihoods, they also pose significant threats to biodiversity, soil organic carbon (SOC) storage, and the long-term ecological balance of the region.

Understanding the interplay between environmental stressors and culturally embedded conservation practices is essential for developing effective strategies to safeguard the Plateau’s ecological integrity and promote sustainable development.

Livestock Management

The Three Rivers region serves as an important carbon sink due to its vast high-altitude and cold grasslands. However, in this fragile ecosystem, grazing has a significant impact on soil organic carbon (SOC) storage and overall ecological stability. Recent fieldwork and related empirical studies conducted in the Saiqing Haradawa Grassland have provided valuable insights into how the carbon sink function can be enhanced while simultaneously supporting the livelihoods of local nomadic communities—particularly through rotational grazing and nature-based ecological restoration strategies.

A meta-analysis of high-cold grasslands on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau indicates that both grazing and enclosure practices can increase the organic carbon (SOC) content in the top 30 cm of soil by 16.5% and total soil nitrogen (STN) by 11.2%; in some cases, SOC in high-cold grasslands can increase by as much as 24.6% [1]. Field monitoring further confirms that reducing grazing pressure continuously improves vegetation biomass and soil carbon storage, demonstrating that lower grazing intensity is an effective approach to enhancing grassland carbon sinks [2].

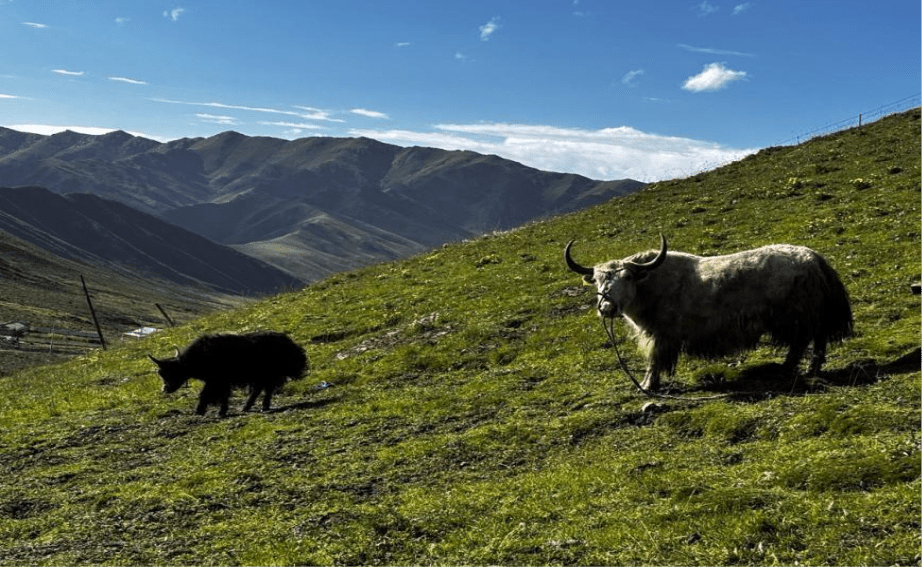

In the Saiqing Haradawa Grassland, local nomadic herders have adopted a rotational grazing system—using summer pastures between April and August before moving to winter pastures. One herder noted, “Sometimes it’s cold, sometimes it’s hot. This year’s grass is okay, but last year’s wasn’t good, because it rained and the grass didn’t grow well.” Such interannual climate fluctuations underscore the importance of adjusting grazing cycles based on changes in precipitation and temperature.

Sonam Gyume, our experienced Tibetan guide, emphasized: “A large number of cattle and sheep will destroy the pasture, and even rotational grazing has its limits.” This highlights that scientific grazing management requires not only spatial rotation, but also strict control over livestock carrying capacity.

However, grazing remains a significant driver of soil organic carbon (SOC) loss. A comprehensive meta-analysis found that grazing can reduce SOC content by approximately 13.93%, with heavy grazing having the most pronounced effect (effect size = –0.15 ± 0.04, p < 0.001) [3]. Overgrazing not only hampers vegetation recovery but also exacerbates soil erosion, reduces root biomass input, and diminishes the efficiency of litter decomposition.

Field investigations in the Saiqing Haradawa Grassland revealed that although winter pastures can still provide edible hay, nomads often purchase and store additional fodder to bridge seasonal gaps. However, without effective control over livestock numbers, this seasonal shortage of forage may lead to the overuse of pastures—ultimately undermining the ecological benefits of rotational grazing and accelerating the loss of SOC.

Nature-based Solutions (NbS) provides a promising path to enhance grassland carbon reserves. Ecosystem modeling research shows that NbS can increase the grassland carbon sinks of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau by 15–21 tagrams (Tg) by 2060 [4]. These measures include replanting degraded grassland, restoring local vegetation coverage, protecting riverbank buffer zones, etc., which can significantly increase carbon reserves above and underground. In Saiqing Haradawa Grassland, local nomads completely rely on natural pastures to raise livestock and do not plant additional supplementary feed. This practice reduces the disturbance of cultivation to the soil, conforms to the NbS principle, and promotes the natural recovery of vegetation, thus maintaining the long-term carbon sink function.

In addition, soil microbial activity plays a critical role in the carbon cycle of high-cold grasslands. Research conducted in the source area of the Sanjiangyuan Region shows that soil organic carbon (SOC) is the primary factor influencing soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC), while plant-derived carbon and phosphorus affect the dynamics of soil microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN) [5]. Healthy microbial communities are essential for organic matter decomposition, nutrient cycling, and stable carbon storage.

In practice, local nomads often collect cattle and sheep manure, dry it for use as fuel, and return a portion of the resulting ash to the soil after burning. This closed-loop nutrient management system not only reduces methane emissions from open-air manure decomposition but also recycles mineral nutrients, supporting the nutrient needs of soil microorganisms. In doing so, it contributes to maintaining microbial activity and enhancing the long-term carbon sequestration potential of the soil.

Tourism

As one of the most popular tourist destinations in China, Qinghai Province attracts over 50 million visitors annually, drawn by its stunning natural landscapes and diverse wildlife. However, while tourism has brought considerable economic benefits to the region, it has also introduced negative environmental impacts—most notably, an increase in the carbon footprint of this ecologically fragile region, often referred to as “the rooftop of the world.”

Globally, tourism contributes approximately 4% to the annual growth of gross domestic product (GDP), but it also drives a significant and often irreversible rise in global carbon emissions. A study by Manfred Lenzen and colleagues investigated tourism-related global carbon flows across 160 countries and found that between 2009 and 2013, the global carbon footprint of tourism increased from 3.9 to 4.5 gigatonnes of CO₂-equivalent (GtCO₂e)—a metric that expresses the impact of various greenhouse gases in terms of the equivalent amount of CO₂. This accounted for approximately 8% of total global greenhouse gas emissions [6].

Through the perspectives of individuals working in tourism-related services—such as restaurant staff, tour guides, and scenic area drivers—valuable insights have been shared regarding the ecological impacts of tourism in Qinghai.

For instance, a waitress at a restaurant near the Qinghai Tibetan Cultural Museum explained that they typically use glass cups and reusable cutlery, but during peak hours (11 a.m. to 2 p.m.), they resort to single-use cups to accommodate the large influx of customers. This reflects the operational compromises made under tourist pressure, which may unintentionally increase waste generation.

A tour guide at the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Natural History Museum highlighted the mounting ecological pressure brought by the surge in tourists visiting Qinghai and Tibet. In particular, mass tourism poses serious threats to the fragile alpine ecosystems, especially in the Sanjiangyuan area, where environmental degradation is accelerating.

One critical concern, according to the guide, is fecal contamination in high-altitude regions. Due to low temperatures and limited microbial activity on the Tibetan Plateau, human waste does not decompose as it does in lower-altitude environments. This accumulation of untreated waste not only disrupts local biodiversity but also underscores the broader carbon footprint left by tourism infrastructure in ecologically sensitive regions. This includes emissions and environmental strain from transportation, accommodation, energy consumption, and waste management systems.

Moreover, insights from the owner of a roadside convenience store provided further understanding of tourism patterns in the region. When asked about seasonal trends at her store, which is located along a highway, she recalled that the number of tourists typically increases substantially during the summer compared to other seasons.

Regarding tourists’ transportation methods, the Tibetan store owner noted that there is usually a similar volume of tour buses and private cars passing by her shop, including both gasoline-powered and electric vehicles. However, it is worth noting that due to local constraints—such as limited infrastructure, cold temperatures, and long travel distances—residents in the area still primarily rely on gasoline-powered vehicles. These contextual limitations highlight the challenges of transitioning to low-emission transportation in high-altitude, remote regions like Qinghai.

The local family also shared their perspectives on the impact of tourism on the carbon footprint in the Sanjiangyuan area. Pengcuo and his family have lived near Lajia Town for three generations. His grandparents were nomads who later settled in this quiet town within the Sanjiangyuan region.

When discussing the effects of tourism in Lajia Town, Pengcuo highlighted a striking contrast in behavior compared to what was described by the owner of the roadside convenience store:

“Tourists frequently litter all around the town, whereas we, the local residents, prioritize and respect environmental protection. We’ve even organized monthly community clean-up initiatives, calling upon neighbors to collect garbage together.”

He also noted that most tourists are transient visitors who stay only briefly in Lajia, primarily to visit Lajia Temple:“Most of the tourists we observe are short-term visitors who don’t stay long. The majority arrive by private cars—tour buses are relatively rare.”

Due to limited direct interaction with tourists, Pengcuo and his family identified littering as the primary and most visible impact of tourism in their area. This perspective offers a grounded, community-level view on the localized environmental pressures brought by short-term tourism in Sanjiangyuan.

Life Style

Traditionally, Tibetans have lived in an environmentally friendly way, and even today they continue to generate relatively low levels of carbon emissions.

In the Saiqing Haradawa grassland, a group of Tibetan families still maintain a simple, traditional lifestyle. They live in tents with roofs made of black yak fur. These tents are not only cool and ventilated in summer but also warm and reliable in winter. When the sun shines, the yak fur loosens to allow fresh air to circulate inside, while during rainfall, the fur tightens to keep water out.

For daily energy use, they rely on traditional sources such as burning yak dung and wood for heating and cooking—methods that make efficient use of available natural resources. In terms of clothing, they usually purchase garments made from common materials like city residents. However, during major celebrations or in extremely cold weather, they wear traditional outfits made of sheep’s wool, which provide greater warmth and carry cultural significance.

Although certain geographic and climatic conditions limit nomads’ access to clean energy sources, settled Tibetan communities have begun adopting renewable energy technologies—particularly solar power. Pengcuo’s grandparents’ home in Lajia Town is a typical example of a settled Tibetan household. They use electricity-powered domestic appliances such as underfloor heating and an induction cooker, and have purchased their own solar panels to generate electricity for household use.

“In the eyes of Tibetan people, disposable items are considered the cleanest, so we usually offer them to guests when they visit,” Pengcuo explained. However, he noted that within the family, they rarely use disposable products in their daily meals.

The family also has its own system for handling old clothing. Instead of discarding worn-out garments, they donate them to local monasteries, which in turn distribute them to individuals in need. Most of their donations are sent to monasteries in the Gande area, as Pengcuo’s grandmother originally came from there. This culturally rooted practice of clothing reuse not only reflects a spirit of mutual aid but also represents a meaningful form of resource recycling and energy conservation.

Waste Treatment

In high-altitude regions, the primary source of waste generated by local residents is household trash. Further interviews and statistical analysis are necessary to support and elaborate on this observation.

At the Saiqing Haradawa Grassland, a typical local Tibetan family provided insight into daily life and waste management practices in the area. To gain a broader understanding, both adults and children were included in the interview process. The hostess—likely the family member most directly involved in daily chores and waste disposal—explained, “We usually rely on traditional methods such as burning or burial. But there are also public trash bins nearby, and we do use them as well.”

She added with some resignation, “Sometimes we simply throw trash on the ground and leave it there.” This behavior was casually observed when an elderly woman discarded a peach peel onto the grass.

While sampling local food, Sonam—our Tibetan guide and the host family’s nephew—commented that although local recycling efforts are limited, they do exist. He noted that younger children are beginning to develop a basic awareness of recycling. However, due to a range of social, economic, and infrastructural challenges, waste management strategies and policies have yet to be effectively implemented at the local level.

In Lajia Town, the home of Pengcuo’s grandparents was once part of a well-known and prosperous extended family. Today, the residents have settled permanently and ceased grazing activities. During a visit to their yard and observation of their daily routines, waste management emerged as a key area of concern.

According to Pengcuo and his mother, household waste is typically first collected in small indoor bins. “We rarely sort the waste,” his mother explained. “Instead, we simply dispose of it in a large outdoor pit, and the government later comes to collect it and transfer it to centralized waste storage facilities.”

Sonam, the family’s nephew and our local guide, elaborated further: “The practice of burning waste can be reduced through recycling. The oil and smoke produced from incineration can be repurposed, and in the end, one ton of trash produces only a small amount of residual ash. This results in minimal environmental pollution. This approach is implemented across counties and towns.”

To gain a broader perspective, younger children in the household were also engaged as interviewers. One young girl remarked, “I’ve seen the elders burn waste using different methods.”

From this case, it is evident that among settled Tibetan families like Pengcuo’s, waste classification remains uncommon, while centralized collection has become the predominant form of household waste disposal. Burning is still practiced to a limited extent, often based on generational habits and convenience.

Pengcuo also pointed out that tourism-generated waste is the leading contributor to environmental pollution in the area. Although the number of tourists visiting their vicinity is relatively small, their presence has nonetheless caused significant ecological concerns. “To be honest,” he remarked, “local residents usually pay close attention to environmental conditions.”

Sonam referenced a local initiative called “No Rubbish Throughout the Area,” which reflects the community’s effort to address these concerns. Wangjia Township, a small settlement that accommodates both local residents and tourists, offers a revealing snapshot of these challenges.

While walking through the area, we encountered a local resident carrying a bottle of yogurt. Cairang, who has extensive experience living in the region, explained that containers such as bottles are typically “burned or buried,” and that waste sorting and reuse remain rare practices in most Tibetan communities.

Near our restaurant, issues surrounding waste management were clearly visible. Despite the presence of a large trash bin nearby, waste was scattered along the streets—and in a surprising turn, goats were seen dragging and consuming the litter.

While environmentally friendly waste disposal practices are occasionally adopted, inadequate waste management is often attributed to both natural constraints and a lack of governmental support and regulation. The former is evident due to the harsh terrain and weather conditions, while the latter requires further substantiation.

In his report The Real Cause Behind Tibet’s Garbage Crisis, Zamlha Tempa Gyaltsen states: “The absolute absence of governance on waste management in rural areas in Tibet has compelled local communities to dump or burn their domestic waste. Even the garbage collected by environmental groups cleaning up nearby mountains ends up being burnt. This is due to the state’s utter failure to provide very basic infrastructure to its citizens.” Tsering Tsomo, who recently returned from a visit to Tibet, also remarked that “there are simply no government waste-collection trucks in rural areas, and the problem is left to deteriorate.”

Sonam, our Tibetan guide, further noted that the proliferation of plastic products has created a sense of helplessness and anxiety among local residents. While such items offer greater convenience and are now widely used, locals often lack both the knowledge and the means to dispose of them properly.

Research by scholars such as Huaqin has emphasized the importance of nature conservation and effective waste treatment in the region [7]. Due to the geographical isolation and logistical difficulties, waste disposal and recycling in these high-altitude areas pose significant operational challenges. However, through the implementation of feasible strategies and enhanced environmental awareness among local residents, these challenges can be gradually addressed.

Religion and Environmental Ethics

The concept of harmonious coexistence between humans and nature is a central tenet of the local religious belief system.

As is widely known, the majority of Tibetan people living on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau are practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism [11]. According to the Buddhist doctrine of Pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination), all phenomena arise through interdependent causes and conditions. This principle underscores that the harmonious relationship between humans and nature is not only desirable, but also essential.

In Tibetan Buddhism, the outer container world and the inner sentient world—together forming the universe—are composed of the five elements: earth (soil), water, fire, wind, and space. This framework reflects the inseparable connection between humans and the natural world. As a guide at the Qinghai Tibetan Culture Museum explained, “The relationship between humans and nature is one of mutual dependence and mutual restraint—an inseparable bond. Mount Kailash, the king of all mountains, is seen as the center of the universe.”

These teachings collectively affirm that harmonious coexistence with nature is a core doctrine of Tibetan Buddhism. The environmental behaviors of local Tibetan residents—such as minimizing waste, limiting hunting or resource extraction, and showing reverence to sacred mountains and rivers—are often deeply rooted in religious beliefs. These behaviors, though not always framed in modern environmental terms, indirectly contribute to the reduction of net carbon emissions.

Thus, the religious doctrine of harmony between humans and nature encourages low-impact lifestyles, restricts overexploitation of natural resources, and nurtures a deep spiritual respect for the ecological systems of the plateau.

Religious beliefs exert a strong normative and binding force on local residents in the Qinghai-Tibet region, deeply influencing their interactions with nature.

Sacred natural sites refer to lands or water bodies that hold special spiritual significance for indigenous peoples and local communities (Wild & McLeod, 2008). These sites possess dual attributes of nature and culture and are considered cultural landscapes—“a joint masterpiece of humans and nature”—which embody the profound interconnection between people and the natural world [8].

In Tibetan cosmology, mountain deities and water deities are the personified spiritual guardians of natural features such as peaks and lakes. The term “deity of mountains and waters” refers not only to these spiritual beings but also to the territory they inhabit. The cultural foundation of all sacred natural sites in the region lies in natural worship. From this belief system arises a wealth of traditional ecological knowledge, such as “Digging on a sacred mountain will bring punishment from the mountain deity” and “Polluting the water of a sacred lake will provoke the wrath of the water deity”.

These behavioral taboos reflect a form of folk ecological wisdom, emphasizing that nature must not be disrupted.

With the introduction and localization of Buddhism in the Qinghai-Tibet region, a distinct form of Tibetan Buddhism emerged—one that expanded upon and institutionalized earlier traditions of natural worship [9]. As a result, ecological thought became a defining feature of Tibetan Buddhist culture, embodied in core doctrines such as “All beings are equal” and “Abstain from killing and release animals” [10].

These beliefs encourage compassion for all life forms and reinforce the ethical imperative of ecological preservation.

Sonam, a local Tibetan, confirmed these beliefs through real-life examples. “If there is both a fish and a yak, Tibetan people would choose to kill the yak to satisfy their hunger,” he explained. “Because both are living beings, but one yak can sustain more people for a longer time—so fewer lives are lost.”

Sonam also described a range of ritual practices grounded in reverence for nature. For instance, Tibetans avoid lying down directly by a river to drink water. Instead, they use their hands to scoop it up, believing that direct contact could pollute the water source and offend the water deity. Similarly, barbecuing is uncommon, as the smoke is thought to carry the scent of meat to the heavens—an act considered disrespectful to deities.

Instead, Tibetans perform the Sang Offering—a ritual in which barley, red dates, sugar, and other non-meat items are burned to produce fragrant smoke, symbolizing devotion and gratitude. These offerings are typically conducted before and after pilgrimage circuits around sacred mountains or lakes, reinforcing the spiritual and ecological dimensions of their relationship with nature.

In summary, strong religious taboos, such as avoiding pollution of sacred waters and minimizing unnecessary killing, contribute meaningfully to biodiversity conservation and reducing activities that would otherwise generate greenhouse gas emissions. These deeply embedded cultural and spiritual practices serve as powerful tools for environmental stewardship, demonstrating that faith-based ecological ethics can play a pivotal role in achieving sustainable coexistence between humans and nature.

The impact of the current changes in sacrificial offerings on the environment.

With the development of society and the growing exchange of cultures, Tibetan communities continue to uphold a deep respect for nature. However, the industrialization of religious items has led to an increase in religious waste, resulting in unintended negative impacts on the environment.

For example, plastic religious objects—now increasingly common—are difficult to decompose. When burned, they contribute to carbon emissions; when buried, they release greenhouse gases such as methane [12]. During observations at Lajia Temple in Lajia Town, it was noted that plastic bags were used to pack items for the Sang Offering (a traditional Tibetan incense-burning ritual). In contrast, during a visit to the home of Pengcuo, a local Tibetan, it was revealed that such offerings were traditionally wrapped in sheepskin bags, which were reusable and environmentally friendly.

Similarly, as noted by Sonam, Tibetan prayer flags (Lungta) were once made of biodegradable materials such as cotton or silk. Today, many are manufactured from modern industrial fibers and synthetic materials, which are non-biodegradable and may contain environmentally harmful substances. These changes, though seemingly minor, have introduced new sources of persistent waste into sacred landscapes.

The modernization of sacrificial practices—such as replacing reusable sheepskin bags with disposable plastic packaging—not only increases solid waste but also adds to the carbon footprint through plastic production and disposal.

By revitalizing traditional, eco-friendly religious customs, the positive ecological influence of faith can be reaffirmed. These time-honored practices offer a culturally rooted, spiritually motivated pathway toward environmental protection—helping to reduce ecological degradation and mitigate carbon emissions, while preserving the sacredness of both ritual and landscape.

The Sanjiangyuan Region serves as a vital carbon sink, yet it is increasingly pressured by grazing practices, tourism, lifestyle transitions, waste management gaps, and changing religious customs. While rotational grazing and nature-based solutions have shown potential in enhancing soil carbon storage, overgrazing and unregulated tourism significantly elevate emissions and place added stress on fragile alpine ecosystems.

Traditional Tibetan lifestyles generally remain low-carbon and resource-efficient, rooted in ecological respect and minimal consumption. However, modernization—coupled with inadequate waste infrastructure—has introduced new environmental challenges, including persistent plastic waste and increased carbon outputs.

Religious beliefs continue to play a positive role in promoting ecological stewardship, yet the industrialization of ritual practices—such as the use of plastic offerings and synthetic prayer flags—has added to carbon emissions and non-biodegradable waste.

Safeguarding the ecological integrity and cultural heritage of the Sanjiangyuan Region demands integrated, multi-dimensional approaches. These include scientific land and grazing management, low-impact community-based tourism, the adoption of sustainable and renewable energy, improved waste treatment infrastructure, and culturally embedded conservation strategies aligned with traditional values and practices. Only through such holistic efforts can Sanjiangyuan continue to fulfill its role as an ecological barrier and climate regulator, while honoring the deep cultural and spiritual traditions of the Tibetan Plateau.

References

[1]Liu, X., H. Sheng, Z. Wang, et al. “Does Grazing Exclusion Improve Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Stocks in Alpine Grasslands on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau? A Meta-Analysis.” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 3, 2020, p. 977, https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030977.

[2]Huang, X., X. Liu, L. Liao, et al. “Grazing Decreases Carbon Storage in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Grasslands.” Communications Earth & Environment, vol. 6, no. 1, 2025, p. 198, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-00496-y.

[3]Yang, H., Y. Zhang, W. Li, et al. “Grazing Disturbance Significantly Decreased Soil Organic Carbon Contents of Alpine Grasslands on the Tibetan Plateau.” Frontiers in Environmental Science, vol. 11, 2023, p. 1113538, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1113538.

[4]Sun, J., Y. Wang, T. M. Lee, et al. “Nature-Based Solutions Can Help Restore Degraded Grasslands and Increase Carbon Sequestration in the Tibetan Plateau.” Communications Earth & Environment, vol. 5, no. 1, 2024, p. 154, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-00435-y.

[5]Dongdong, C., L. Qi, H. Lili, et al. “Soil Nutrients Directly Drive Soil Microbial Biomass and Carbon Metabolism in the Sanjiangyuan Alpine Grassland.” Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, vol. 23, no. 3, 2023, pp. 3548–3560, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-023-01357-6.

[6] Lenzen, Manfred, et al. “The Carbon Footprint of Global Tourism.” Nature Climate Change, vol. 8, no. 6, May 2018, pp. 522–28. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x.

[7] Zamlha Tempa Gyaltsen. “The Real Cause behind Tibet’s Garbage Crisis – Central Tibetan Administration.” Central Tibetan Administration – Restoring Freedom for Tibetans, 4 May 2018, tibet.net/the-real-cause-behind-tibets-garbage-crisis/.

[8]杜爽,韩锋,马蕊.世界遗产视角下的国外自然圣境保护实践进展与代表性方法研究[J].风景园林,2019,26(12): 85-90.

[9]宗晓萌.阿里地区的神山圣湖崇拜及其寺庙建筑[U].山西建筑,2019,45(1):5-6.

[10]张慧,林美卿.藏传佛教的生态思想及其当代价值[J].云南社会主义学院学报,2018,20(4):105-110.

[11] Encyclopedia Britannica — Tibet: Ethnicity, Religion, and Culture

[12]TRINE BROX, Plastic Skinscapes in Tibetan Buddhism,2022.file:///C:/Users/26966/Downloads/Brox+CJAS+2022_40(1)%20(3).pdf